Exclusive interview with co-founder John Brownstein and the full history of HealthMap in one timeline visualization.

The HealthMap project started 9 years ago in a humble research environment and quickly grew to one of the most important public health technology and communication platforms for infectious diseases. But that’s not all. Now the team has started applying the core concept to wearable technology and work has been done in the pharmaceutical drug space, too. The manner in which all of this fits together is shown in the timeline we created below.

In an interview, John Brownstein, co-founder of HealthMap, explains what drove and guided him along his way.

nuviun: Why did you start HealthMap?

John Brownstein: I spent time in Africa to research infectious diseases. In my PhD I tried to combine all my interests—particularly I wanted to become active in the distribution and the impact of infectious diseases. I also noticed that field-research wasn’t really my thing, and that I just didn’t have what it takes to be a really good field researcher. I then became also really focused on adopting risk maps for infectious diseases.

Finding that the US government was just not sharing (enough) information, Brownstein came to a point in which he began to work on the data site himself—starting in the clinical context of big data. Brownstein realized that government data was highly restricted and hard to access. In addition to the restricted access, its format made it difficult to use, he said.

nuviun: Where and how did you find content to use?

John Brownstein: There were all these chat rooms and all that data about disease events and nobody was organizing that content in any public way, so we created HealthMap.org nine years ago. We intended to organize all this content for infectious diseases and public health events and build a repository of freely accessible information. In fact it is actually kind of funny that now the government is asking us for our data. It really brought us to the use of new methods like machine learning, for example.

nuviun: What was the first response from the public, and how did you grow HealthMap?

John Brownstein: We started at a time when public health wasn't really sexy as far as technology concerns. We managed to create a somewhat nice website and introduced data visualization, which got us ahead of everything that has ever been done in public health to this point.

We took a very engineering focused consumer-web approach for public health, which got us a huge amount of interest in the public domain. Then WIRED wrote about us which got us much broader recognition. Next, Google came and took an interest in us and funded us later. With funding, we grew from only two people to a team of 45 people including all software developers and researchers. We also collected funding from all sorts of other sources including foundations and almost every government agency. After this kind of success HealthMap became a go-to site for emerging public health issues.

nuviun: What about the importance of mobile and social media?

John Brownstein: We finally were able to get into new areas as technology changed, as the mobile phone emerged. We created the first public health app. Social media came into play and conducted some of the first examples. The Twitter data analysis we conducted which was applied to public health was one of them. Then there was Google Flu Trends.

nuviun: You and your team are pushing the boundaries of public health tech innovation. What’s next?

John Brownstein: Now we are experimenting with the wearable device area, and new mechanisms to deliver disease prevention. Just now we are partnering with Uber to do flu prevention.

nuviun: Tell us about the HealthMap-Uber collaboration.

John Brownstein: It was my idea. We got in touch with Uber and we expressed interest to partner up. Amazingly enough they wanted to work with us.

Uber launched UberHealth in collaboration with HealthMap. For a full overview, go to Uber’s blog: http://blog.uber.com/health

nuviun: What’s your secret? Is there a HealthMap innovation strategy?

John Brownstein: Every time there's a change in the information and web landscape to innovate, we try to partner and work with those organizations that appear—off the ground. Whether it’s Twitter or Yelp, Facebook or Google, we would try to use the data coming from those organizations and apply it for new public health applications.

nuviun: John, do you think digital health is at a point where technology can start advising people about how to live their lives, or do you think its still a long way to walk?

John Brownstein: I think we are partly there. There's a subset of the population, the early adopters, who use web devices. They drive the trend of digital health, not particularly in public health, but in general. I think we are on the right track towards adoption. Whether it’s, for example, the Apple Watch—or all the other devices— they will essentially contribute to help people to get a better sense of how one should change behavior, how to change the broader view on what's happening in correlation, and help to see how one compares to other people.

nuviun: In October, Epidemico Inc., owner of HealthMap, was acquired by Booz Allen Hamilton. First of call, congratulations. Are there any consequences?

John Brownstein: We are an academic research group at Harvard Medical from Boston Children's Hospital, running a research group to do R&D and public health research. We spun off an entity called Epidemico Inc. that commercializes the licensing of our technology. This way we can be dealing much more with the commercial side, dealing with data sales, and it allows us to develop tools for the government. That company was bought by Booz Allen which opens great opportunities. It allows us to go to places we would have otherwise never gone to and it is good for our infrastructure in order to scale up.

For more info on the acquisition, check the bizjournals.com article.

nuviun: John, you mentioned scaling. In terms of growth into new verticals, what’s your strategy?

John Brownstein: We definitely want to go into new verticals. We have another product called MedWatcher. MedWatcher is on the drug safety side of things and uses the same technology. It looks at people's discussions around pharmaceutical products and how they provide new data to regulators and the industry.

MedWatcher is a free mobile app and web application which allows users to learn about the side effects of pharmaceutical drugs, medical devices, and vaccines— and allows them to easily report adverse events to the FDA. The app (web, iPhone and android) is officially recognized by the FDA. When a user submits a report using the mobile app or website, MedWatcher verifies and formats the information so that it can be sent to the FDA. It also publishes a de-identified version of the report to MedWatcher so that other users can learn about the side effects posted.

nuviun: Are you also expanding geographically?

John Brownstein: We actually have a project on now with the EU, and working also in close collaboration on a project with the UK (government) to develop something very similar to what we offer to the EU. There are many new opportunities. Another area we are active in is the supply chain and social disruption. The black markets is one example. But there are many different angles where our machinery can operate and add value. We haven’t reached the ceiling yet with our existing domains. The countries we are operating in at the moment still offer opportunities to do so much more within and outside our current verticals.

nuviun: What's the secret recipe for your success? Why did HealthMap become so successful?

John Brownstein: It's a variety of tools. For one, it’s this highly customized taxonomy of online conversations, which we translate into code. We identify how people refer to illness online and we translate it into a format that makes sense, from both a public health and regulatory perspective. That takes a huge amount of work. What we do with machine learning is to distinguish between what is useful data and what isn’t—including the process of clustering information that is on the same topic and removing duplicate information. It is also our ability to geo-locate from free text. There are a bunch of pieces to the equation. Other groups might do this maybe in a more general way. What we did was to build this deep knowledge and taxonomy for public health and organized it for web content.

nuviun: What is the plan for 2015?

John Brownstein: Building collaborations to build better infrastructure, we will work with collaborators on mobile data collection. I think we're very excited about partnering with [medical] device companies. We're building APIs these devices can talk to in order to provide insights to consumers. For example we are working with a device company that does temperature monitoring. We can use our APIs to provide feedback. It might help to give advice to a patient reminding her that maybe she should call a doctor if her temperature rises, or in the case that there is a certain reaction to the medication in use. We are getting interested in some of the passive data collection too, which comes from an individual. A hybrid of passive and some active input is really interesting. I think we're definitely pushing on in the coming year.

nuviun: Can you offer advice to tech entrepreneurs intending to innovate in healthcare and big data?

John Brownstein: We took a lot of heat initially for building a system that was relying on non-traditional data and we were really transparent from the start. I think there is a lot of value in putting yourself out there and developing a tool everyone can see.

Personally I have seen better concepts coming out when people are open about their ideas. Concepts that were open and got feedback from the beginning, instead of keeping an idea in an incubator for a year before launching it, might be more successful. Being scared that one’s idea is being stolen is not a good reason to not push a concept. This isn’t different for healthcare. My advice is to put your concept out there and people will react. Once people start to compete with you, it is a rather good sign—as it shows that there is an opportunity. At HealthMap we also have seen competition, but it never really hurt us and only drove us further.

nuviun: John, what do you think was HealthMap’s greatest win?

John Brownstein: I wouldn't say there is one big success. We had a few events where our system picked up something very early, but that's only part of the equation. We had a big uptake for the events around Ebola, even before we got great attention from the swine flu we reported on, for instance. Our ability to move quickly for major public health events and provide customized use is one way to describe success for us. In addition, ensuring that our products meet the needs of multiple stakeholders simultaneously is a big thing for us.

HealthMap and the Ebola Outbreak

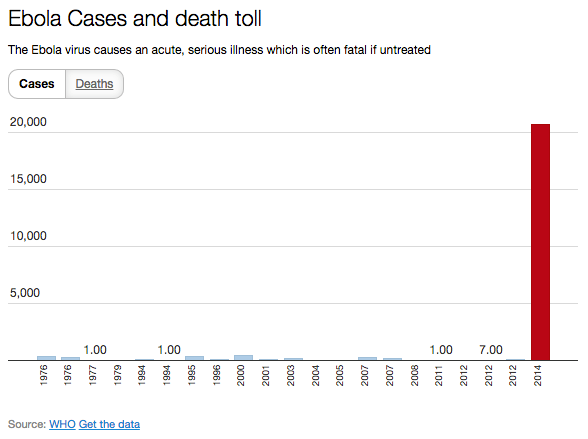

The Ebola virus took more than 8000 lives in 2014 and is considered as one of most aggressive viruses in recent history. For the developed world and many of us, the virus was never as real as it is now—as deadly viruses were mostly known from Hollywood movies, such as Mission Impossible II. With a survival rate of only about 50%, the Ebola virus became scary reality for both developing and developed countries, but was particularly devastating in countries in West Africa. The fact that Ebola isn’t new, and that the virus killed before the outbreak, is evidenced in the graphic below:

HealthMap’s work regarding the Ebola outbreak is the latest example of how online technology can support the ability to detect and track outbreaks. HealthMap picked up on the outbreak and alerted key agencies in the U.S. government four days before the World Health Organization made an announcement (source: TIME.com).

One of the big advantages that HealthMap possesses is its speed. It searches within a pool of social media, non-official online reports, and online channels. Because it could make a connection and offer a clue about the diagnosis from what people said—in combination with what the media was reporting—it was able to spot Ebola faster. In the case of the March 19 news report in the media outlet from Kenya, theStandard News, the team at HealthMap could add a new piece to the puzzle because they saw the connection between the Ebola virus, its symptoms, and the cases reported. You can check out HealthMap’s Ebola timeline for the geographical spread here.

One of the latest examples (January 9th) HealthMap reported on is a mysterious outbreak of HIV in a village in Cambodia’s Battambang province, where after 100 people tested positive for HIV within a week, people started to panic. The strange thing, as with most HealthMap initial reporting, was that the cause or the source was unknown. But with the continued development of agile tools such as this to provide early warnings, digital surveillance can help to predict and contain disease outbreaks.

About John Brownstein

Co-Founder of HealthMap, Brownstein is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, and has joint appointments in the Children's Hospital Boston Informatics Program and Division of Emergency Medicine. He was trained as an epidemiologist in the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health at Yale University where he received his PhD. Dr. Brownstein works on novel statistical modeling and medical informatics approaches for accelerating the translation of public health surveillance research into practice. You can learn more about his work on HealthMap.

Ben Heubl is nuviun's data journalist who specializes in data visualization and writes about health and tech innovation. You can follow him on Twitter @benheubl.