Healthtech journalists Ben Heubl and Nick Saalfeld discuss how less privacy could lead to better health.

Good data helps us to make good decisions in life – and that includes health. A simple example is the nutrient and calorie information on the food which we eat.

We have more health data available to us than ever before. In a September 2014 survey, analysts TechnologyAdvice report that over 25% of US adults are now using either a fitness tracker or smartphone app to track their health, weight, or exercise.

As well as calorie-counting, a raft of devices like the FitBit or Apple’s new watch and HealthKit system are going to put more reliable and easy-to-understand data about ourselves at our fingertips.

And we need this personal data because we’re all different. Even that calorie information is pretty variable from person to person – and certainly from society to society.

But lots of data doesn’t mean useful data.

- Useful data is reliable, which is why tomorrow’s weather report is better than next month’s weather predictions.

- Useful data is easy to understand, which is why financial decisions are sometimes so hard to make: even information which is perfectly correct can be horribly confusing.

- And useful data is relevant: it must mean something to me. Calorie counts and heart rates mean different things to triathletes than the bedbound.

We go to the Internet, not the doctor

Thanks to the Internet, curious patients have plenty of data at hand. 70% of Internet users get health information online, and Ulrike Rauer, DPhil (PhD) Candidate at the Oxford Internet Institute says this has been constant for seven years. But the Internet is a minefield. Says Rauer, “A lot of people are aware that sources online differ in trustworthiness and take things they read online with a pinch of salt. In practice, some people end up more worried."

David Spiegelhalter, Professor of the public understanding of risk at Cambridge University, has researched the relationship of health with the media. In a paper he says,

“people generally rely on news reports to learn about emerging science and health issues rather than sources such as general practitioners... the news media are thus a very important factor in the transmission of knowledge about risk issues.”

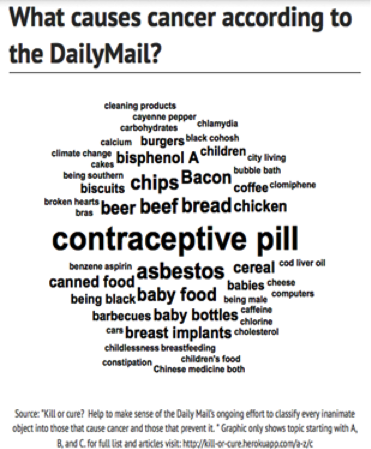

Unfortunately, dodgy online information is not just the preserve of the pill-hawkers and conspiracy theorists. The mainstream news media is just as unreliable. Here, for example, are just the A-C of things which cause cancer, according to the Daily Mail.

The global research team: aggregated social data

Today, however, we are on the brink of being able to contribute to, and benefit from, a world of useful, socially-sourced health data, which will be both reliable and easy to understand.

Take an example from the online social media space: Healthmap. Via online news aggregators, eyewitness reports, expert-curated discussions and validated official reports, Healthmap achieves a unified and comprehensive view of the current global state of infectious diseases and communicates it with admirable simplicity to the reader.

Meanwhile, according to WIRED, the Swedish weight-loss app Lifesum analysed the health habits of 100,000 users from their database of 6.5m downloads and found out exactly what those people ate and what kind of work-outs they did. Knowing what one group of people eats can be used to better advise another group of people who really need to know—including people who don’t have the Lifesum app.

The next step in getting advice we can act on might be to start merging aggregated public health data and news sources with our personal data to support better public health recommendations. Dr. Mohammad Al-Ubaydli, CEO at Patients Know Best says,

“digitisation of data allows mass customisation of the best care. The availability of healthcare data digitally means software algorithms can finally compute at the point of care, with the patient, for the patient.”

Bill Davenhall, for example, has been writing about “geo-medicine” since 2009. He wants to improve physicians’ diagnostic techniques by collecting patients’ geographic and environmental data and merging it with their medical records. Davenhall goes so far as to recommend increased cancer screening in geographical cancer hotspots, and says that location—one data point alone—can revolutionise health provision.

Privacy freaks might want to stop reading about now.

In a landmark article, WIRED’s Madhumita Venkataramanan explains not just how our personal data is collected, bought and sold; but also how aggregation of this data makes us identifiable and our actions predictable. This on the same day as New York outdoor media business Titan was forced to switch off mobile tracking devices in phone booths. Venkataramanan also rightly points out that the fact that the NHS sells hospital data to commercial organisations is at best a foolish betrayal of the expectations of the UK public.

And yet, perhaps these commercial aggregation techniques are exactly what could allow us to target healthcare information more effectively.

- Should everyone be petrified of the Ebola vector? Probably not.

- Does everyone respond in the same way to anti-smoking or anti-obesity campaigns? Definitely not.

- Would health messaging be more effective if you knew I was on my way to work; or the gym? Without doubt.

This is the sort of thing which business does every day. Plus, in healthcare, it seems that privacy is not such a major concern: the TechnologyAdvice survey on wearable health monitoring devices reports that data privacy was only cited by a meagre 10.5% of non-adopters of wearables as a reason for holding back.

Healthmap and Lifesum show us that crowd-sourced data can be reliable. The wearables and “Quantified Self” revolution promises that ever more of that data will be available. Apple’s reputation for user interface design, along with the elegance of displays like Healthmap’s, promise an ever-simpler ability for patients to understand what they are looking at. But the third criterion of usefulness—relevance—demands we tackle our data fears.

A new incentive might be coming: cold hard cash. The TechnologyAdvice report concludes that “The greatest opportunity for increasing adoption of fitness and health tracking lies with insurance companies. Over 57 percent of adults indicated that the possibility of lower premiums would make them more likely to use a fitness tracking device...

“If healthcare providers worked in tandem with health insurance companies, both stakeholders could benefit from the collected population health data.”

Even in the UK and elsewhere in Europe, where insurance is much less prevalent at the heart of healthcare delivery, it may make economic sense to incentivise every citizen to power up their smartphone and put the latest personalised health advice on everyone’s wrist.

Ben Heubl is a data journalist who writes about health and tech innovation. You can follow him on Twitter @benheubl.

Nick Saalfeld is a healthtech journalist and marketer. You can follow him on Twitter @nicksaalfeld.

The nuviun blog is intended to contribute to discussion and stimulate debate on important issues in global digital health. The views are solely those of the authors.