London’s tech entrepreneurship ecosystem has encouraged its business owners to master a set of unique skills. Think Eric Ries’ lean startup approach and the ability to prototype fast and fail cheaply. Or the creation of valuable partnerships, bagging investment and growing at warp speed towards an exit. These lessons made TechCity one of London’s key tech-sector support organisations.

Now, the Mayor of London wants to do the same for healthcare, with MedCity. The mission is to support health and biotechnology in London, Oxford and Cambridge. Sarah Haywood, acting COO of MedCity Ltd says: “MedCity wants to learn from TechCity”. At a recent event “MedCity x TechCity: London’s Winning Duo for Digital Health Start-ups?”, a panel of key healthtech influencers covered some of the lessons new health entrepreneurs can learn from their tech cousins. Here are just three of them.

Lesson 1: Prototype, Test and Fail Cheaply

Creating a sophisticated biotech solution might not sound cheap. And it isn’t. Development and regulatory approval costs are high. However, London’s tech entrepreneurship community has mastered the ability to prototype fast and at low cost, always seeking to shorten each cycle or iteration. And in case of failure, they cut the cord much earlier on. Effective prototyping is one of TechCity’s core mission statements.

On the panel, Haywood mentioned that access to clinicians was a recurring need raised by healthtech entrepreneurs. In order to create workable products and services, it’s essential that developers have access to the people – clinicians and patients – who will ultimately use these new innovations. Haywood says MedCity wants to help engineer and facilitate these trials. If this can be managed cheaply and effectively, as happens in the non-regulated tech world, than we can expect to see more innovations succeed more rapidly in health and biotech. Dr Nasrin Hafezparast, Co-founder & Technology Lead, Outcomes Based Healthcare says that healthtech entrepreneurs ‘just need to do’, and TechCity offers a template environment for starting up fast without spending years on research.

Lesson 2: Learn about investor goals

Last December, a report on TechCity stated that the brand has generated rapid growth - from being a local initiative, blossoming into a mature digital capital for Europe in only three years. This has included better infrastructure, plenty of job creation (e.g. Pivotal, Samsung Electronics UK) and, above all, major investments by global technology brands.

As many tech investors are waking up to the investment opportunities in digital health, MedCity entrepreneurs can improve their financing strategy by getting a better handle on what tech investors are looking for.

For example, Dr Vishal Gulati, Venture Partner at DFJ Esprit says that if a digital health business model is predicated on the NHS as a single main customer, then, despite its size, the majority of investors will frankly not be interested in investing, as scalability and growth will be perceived as severely limited.

As a bridge between start-ups, investors and the existing health and pharma infrastructure, MedCity can help push for regulatory change. It can encourage NHS bodies to make more independent decisions. And it can build marketplaces which support the development and integration of private healthcare services.

Lesson 3: Entrepreneurs feed on data

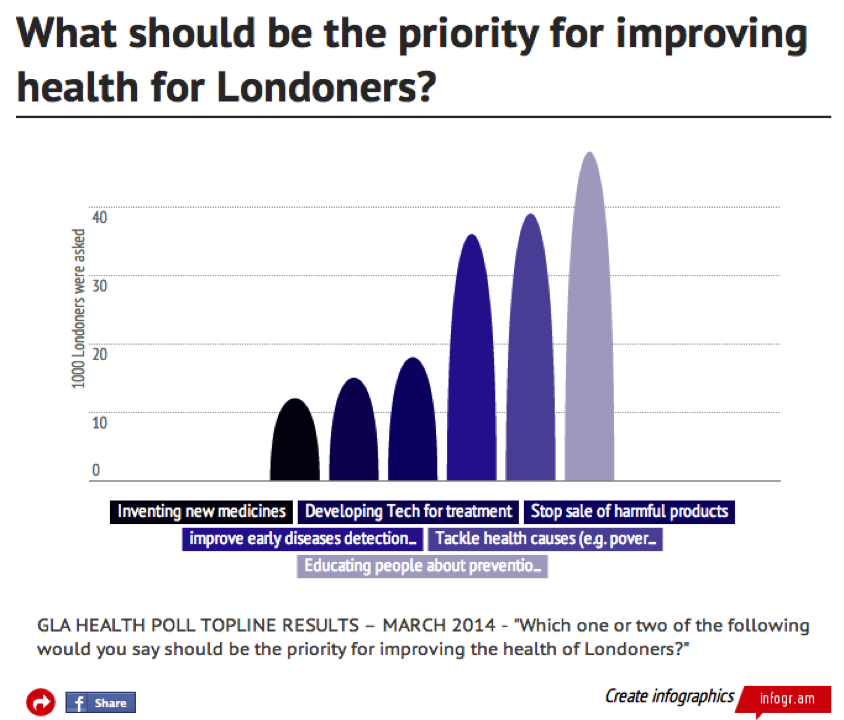

To find opportunities, entrepreneurs look for a gap in the market; and it’s no different in healthcare. At the MedCity x TechCity panel, audience questions confirmed that innovators have a strong appetite for data which generates reliable commercial insight. Gulati mentioned the missed opportunity of Care.data - and how it has held back the health entrepreneurship community. Examples like the Health Poll (where 1000 Londoners where asked about London’s quality of health access) by the London Health Commission can really open innovators’ eyes on how to find and exploit needs.

Graphic: Example of how information can help health innovators to spot a market opportunity:

Haywood agreed that working closely with partners like the London Health Commission to provide valuable insight is part of the deal. Haywood also highlighted the challenges of understanding and engaging with the fragmented NHS. She says the foundation of the Academic Health Science Networks (AHSNs) will help to address the problem of understanding who will procure innovation.

MedCity’s launch in early 2014 is part of London’s £4.1 million bid to develop the most important biotech cluster in the world. In comparison, TechCity banked a £15.5 million funding package from the government’s Technology Strategy Board to help innovative businesses to grow and scale. What MedCity might also be able to learn from TechCity is the ability to arrange effective funding and development competitions. At the moment, TechCity has plans for £12.5m in research and development funding competitions to boost digital and computing technologies; and MedCity would benefit from the same reach.

How closely the health and biotech sectors mirror the tech startup scene remains to be seen. But TechCity can certainly be a model for MedCity: in particular the ability to build and scale faster than traditional healthtech and biotech businesses have currently achieved. If MedCity can help to overcome the barriers of cost and time, reduce the cost of failure, create more transparency and better partnerships for fast-growing businesses, it could achieve exactly the same sort of success as its big tech brother.