Researchers develop a type of “electronic skin” that can detect lumps in breast tissue that are still too small to be detected on a manual breast exam.

In breast cancer screening, mammography has been shown to lower death rates by as much as 20 percent, according to the World Health Organization. But mammography, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are costly and resource-intensive.

Among cheaper screening alternatives—breast self-exam (BSE) is of uncertain benefit, while clinical breast exam (CBE) may lower the incidence rate of advanced-stage breast cancer.

But while health professionals performing a CBE can expertly identify small lumps—they can usually only detect them when they are as large as 21 mm (4/5 of an inch) long and 8 to 18 times stiffer than surrounding tissue.

Electronic Skin Enhances Detection

To overcome this limitation of palpation, researchers at the University of Nebraska have developed an “electronic skin” that can detect tumors less than 21 mm in size.

Detecting tumors less than half that size can almost double the survival rate of breast cancer patients, according to a press release.

Researchers Ravi F. Saraf and Chieu Van Nguyen created “a kind of electronic skin out of nanoparticles and polymers that can detect, ‘feel’ and image small objects.”

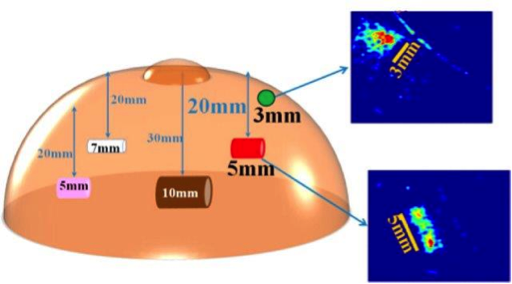

In their experiment, they used a silicone breast to embed small objects as tiny as 5 mm and buried them as deep as 20 mm. They then applied the film and pressed the “electronic skin” against the breast model with the same pressure a care provider would apply to a real breast during a clinical exam.

A silicone breast model was used to test the electronic skin.

Credit: American Chemical Society. Used with Permission.

As detailed in the findings of the study, funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and published in ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, the researchers were able to not only successfully image the tiny lumps, but also clearly note their shapes—which is important in order for doctors to determine if a lump is cancerous or not.

“Some devices already mimic a manual exam, but their image quality is poor, and they cannot determine a lump’s shape, which helps doctors figure out whether a tumor is cancerous,”according to the press release.

Using the thin-film tactile device on a real breast during a CBE can help clinicians detect minuscule tumors 5-10 mm in diameter that are smaller than what the unaided human touch can detect.

This new kind of sensitive medical imaging can increase the survival rate by as much as 94 percent, the researchers said. It may also be able to detect early signs of melanoma and other cancers in the future.

This “electronic skin” can drastically enhance the effectiveness of breast exams, especially in developing countries where breast cancer is often diagnosed in late stages.

It has the potential to improve diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. As the WHO pointed out, “early detection in order to improve breast cancer outcome and survival remains the cornerstone of breast cancer control.”

Dermals are Emerging

Dermals, similar to the one described above, have been created to measure vital signs such as temperature and blood pressure, muscle activity, and even the ability to interface with a computer.

As a separate article describing stretchable electronic devices said,

“One major advantage of skin-like circuits is that they don’t require conductive gel, tape, skin-penetrating pins or bulky wires, which can be uncomfortable for the user and limit coupling efficiency. They are much more comfortable and less cumbersome than traditional electrodes and give the wearers complete freedom of movement.”

Electronic skin, patches and tattoo-like sensors are the next evolution in digital health.

Health data in the future will be increasingly tracked not by devices that you “wear” but by skin patches that can record vital signs, scan medical images and perform point-of-care therapies.

As John Nosta said in this interview,

“the devices will evolve to become less of a watch that you wear, and perhaps a dermal or a patch or an implant—or will ultimately completely go away to be absorbed into the fabric of our lives.”