Digital news, social media, and big data complement the traditional methods for tracking and reporting communicable diseases, such as Polio and Ebola.

When a child develops a sore throat, fever, and vomiting, parents worry. Parents of sick children worldwide do everything they can to soothe their child, reduce pain, manage the fever, and encourage rest.

If the illness lasts longer than a few days, physicians may be called. Neighbors may bring soup. Parents and other caregivers, who are most exposed to the virus, visit the pharmacy.

The virus, which was once fairly contained in a household, could be everywhere—even in sewage. Even if all household members washed their hands and tried to contain the virus, communicable diseases can spread quickly into epidemics without adequate warning.

Disease Surveillance for Outbreak Response

Some viruses, such as Ebola, polio and certain influenza strains, require careful monitoring by public health workers and epidemiologists. Disease surveillance is the ongoing, systematic collection, interpretation, and dissemination of health-related data.

Disease surveillance is used to predict or detect outbreaks of communicable disease, identify high-risk populations, determine the burden of the disease, monitor the effectiveness of immunization programs. In short, disease surveillance is essential for public health.

WHO data is estimated based on vital registration data, immunization data, and clinical studies. WHO reports often underestimate the number of disease cases, but provides useful trending information, allowing public health workers to understand the epidemiology of the disease.

Used to guide immunization programs and set priorities, disease surveillance data can be used as an early warning system to identify public health emergencies. A recent Lancet article, Digital Surveillance for Enhanced Detection and Response to Outbreaks, compares the surveillance data provided by the World Health Organization to real-time digital information monitoring.

According to the authors, for all seven WHO-reported polio outbreaks in 2013 and 2014, digital reports using data analysis and illness mapping preceded official reports by an average of 14.6 days.

The article highlights two significant outliers, time lapses between outbreaks of polio in communities and release of official WHO reports.

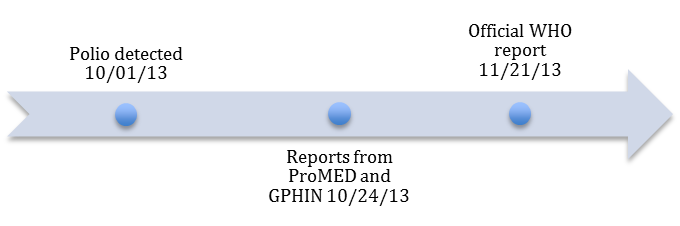

Cameroon Polio Outbreak of 2013 - Number of days from disease detection to WHO report dissemination: 51

Source: nuviun, Lancet data

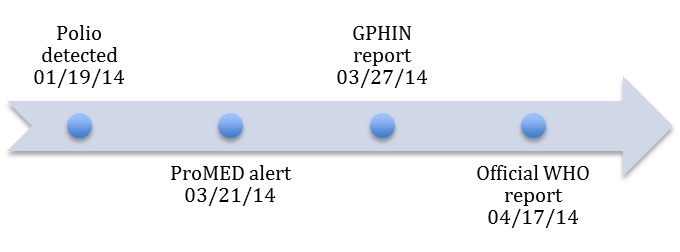

Equatorial Guinea Polio Outbreak of 2014 - Number of days from disease detection to WHO report dissemination: 88

Source: nuviun, Lancet data

While the average time lapse of two weeks might not seem significant, when it comes to the spread of communicable diseases, it can be a lifetime. Fourteen days is enough time to initiate disaster planning and recovery, to send resources—like supplies and healthcare providers—and to issue travel warnings.

International Disease Tracking Standards

The WHO sets international standards for disease tracking. According to the WHO, the gold standards for polio surveillance involve monitoring two data points: the number of Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) cases, and systemic environmental sampling. Environmental sampling confirms the presence of wild polio in the absence of paralysis. There are four steps to nationwide surveillance of AFP:

- Finding and reporting incidences of AFP

- Collecting and transporting stool samples for analysis

- Isolating and identifying polio in the lab

- Mapping the virus.

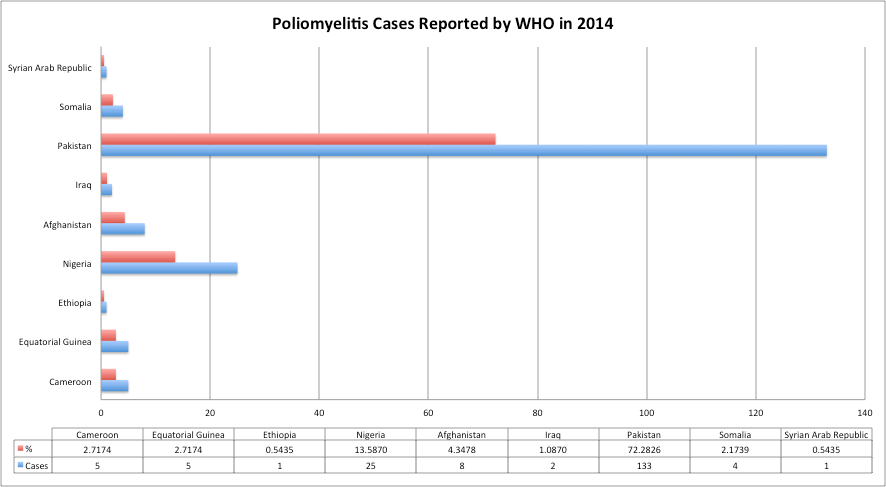

The following chart reflects the number of polio cases in 2014 as reported by the WHO:

Source: nuviun, WHO data

The WHO information gives us 184 cases worldwide, most of them in Pakistan. However, searching HealthMap gives a much different perspective. HealthMap is a real-time search engine that searches all kinds of information sources, including social media and digital news sources, including one article from Dunya News, putting the number of polio cases reported in Pakistan in 2014 at 295.

Web-Based Warning Systems Complement Standard International Surveillance

According to the WHO, more than 60% of the initial outbreak reports come from unofficial informal sources, including sources other than the electronic media, which require verification. Yes, rumors, purchases of hydration salts or fever reducing medications, and social media posts are potential sources of disease data.

Web-based early warning systems, such as HealthMap, BioCaster, Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN), MedISys, and ProMED-mail, collect disease-specific data from informal sources such as local news and social media. Web-based queries and participatory systems also produce cost-effective data for disease surveillance.

These early-warning systems are constantly searching the ethers for reports of communicable diseases. As mentioned in the Lancet article, systems like HealthMap are updated in real-time, providing a clearer picture of diseases internationally.

Jenn Lonzer has a B.A. in English from Cleveland State University and an M.A. in Health Communication from Johns Hopkins University. Passionate about access to care and social justice issues, Jenn writes on global digital health developments, research, and trends. Follow Jenn on Twitter @jnnprater3.