In a drafted document that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently released, the US federal agency clarifies its thoughts about which types of wearable tracking devices will be under its watch.

Good news for wearable health trackers. The FDA discusses wearable tracking devices in their latest draft guidance, drawing a somewhat clear line between what kind of devices will be regulated, and which won’t. This is good news for the industry and health tech startups alike—as lower regulatory hurdles will reduce business risk and increase investors’ confidence in this emerging growth sector.

Source: FDA

In a drafted document that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently released, the US federal agency clarified its thoughts about which types of wearable tracking devices will be under its watch. Those which wouldn’t fall under the authority of the FDA will not automatically receive market approval. We put together 5 of the most important facts about the draft guidance document.

1. Devices treating specific medical conditions

Wearable devices being regulated are devices that promote themselves as a way to treat or cure specific conditions. A typical example is a glucose monitoring device which is aimed for a specific condition—diabetes.

The wording of “general wellness and general wellness claims” is important in this context. The Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) refers to general wellness products as products that:

“(1) are intended for only general wellness use, as defined in this guidance, and (2) present a very low risk to users’ safety.”

General wellness products won’t be regulated by the FDA—as long as those two criteria are met.

2. FDA – Hands off: Devices for overall health and wellbeing

The fact is, being more active and participating in sports can contribute to better health and wellbeing. There are hundreds of studies to support this, and isn’t an issue that doctors or consumers would argue about. The key here is that there is little risk to the consumer if a device supports the user in obtaining such goals. The thinking of the FDA is that devices that are concerned with promoting "general wellness"—such as a healthy lifestyle—and include claims well-supported by science do not present much of a risk to users.

Features that support the wearer’s overall health can include heart rate monitoring, location tracking, and accelerometer features—which provide the ability to count and get feedback on steps (or similar activities). These won’t be regulated. In contrast, a health tracking device specifically concerned with obesity will likely be regulated by the FDA. Key language in the guidance to make this determination includes the fact that device benefits “do not make any reference to diseases or conditions.”

Also in this context, the following passage is important:

“The second category of general wellness intended uses is comprised of two subcategories:

1) intended uses to promote, track, and/or encourage choice(s), which, as part of a healthy lifestyle, may help to reduce the risk of certain chronic diseases or conditions; and

2) intended uses to promote, track, and/or encourage choice(s) which, as part of a healthy lifestyle, may help living well with certain chronic diseases or conditions.”

Here, the benefits obtained from a healthy lifestyle that may be achieved through device use may help to “reduce the risk or impact of a chronic disease or medical condition”—but aren’t used to diagnose or treat them.

3. The guidance document is not written in stone!

The FDA's guidance document is only to be seen as a recommendation, and does not yet establish any legally enforceable responsibilities. Rather, it expresses the FDA’s current thoughts on the wild discussion of wearable health devices.

Whether this document will eventually emerge strictly based on FDA thinking, or a well-lobbied push from the industry—where Apple, Samsung and Google want to dominate without legal barriers—isn’t clear.

4. Wearable tracking startups: Don’t open the champagne bottles just yet.

This guidance document is a step in the right direction. But we aren’t there yet. The startup industry has been waiting for more clarity for quite a while. More transparency means an increased chance at winning over investors—and ultimately customers. One recent example of how toxic uncertainty in the regulation approval process can be is evidenced by the experiences of the personal genomics company, 23andMe.

Last November, 23andMe received a letter from the FDA which ordered the company to immediately discontinue marketing its testing kit and personal genome services. The agency said the test results offered medical advice and therefore required regulatory approval. Startups need to do their homework before launching.

5. Beware of the Risk

What should you consider if you are planning to launch a wearable device company and don’t want to be regulated by the FDA? Keep in mind that the agency is most concerned with the risk posed to the users and possible adverse events. This means that the risk of something going wrong with the use of your device should be calculably low. Last summer, the agency released a beta version of the API showing the number of adverse events, from drugs to medical devices. It is a collection of data about product recalls, documentation on product labeling rules, and the adverse event reporting system (covering any report of an adverse reaction or error with medicine).

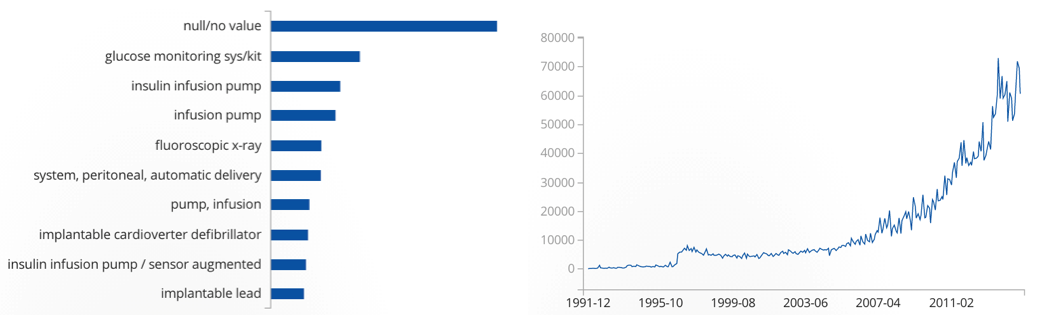

Below, see a graphic from the FDA’s API that shows the number of adverse events related to medical devices. Wearable health devices that come close to the product definitions associated with most adverse events will certainly be regulated. As one can see, there’s good reason for that.

Adverse events from medical devices, per category (left) and over time from 1991-2015 (right)

Records matching US adverse event reports: 3,867,173. Source: https://open.fda.gov/device/event/

That the US saw an exponential increase since 2010/11 in adverse events related to medical devices might have to do with an increased number of high tech medical device products on the market. It’s also possible that the numbers increased simply because more people had access to medical devices overall.

In addition, wearable trackers as we know them are unlikely to be injected or placed inside of your body. When that’s the case, the risk of an adverse event is much lower.

The bottom line? It’s wonderful news for startups and companies developing wearable health and wellness devices that the FDA is starting to be more clear about what will fall under their regulatory control and what won’t. This could have an interesting effect on the investment market for wellness and fitness trackers. Investors might become more relaxed as the regulatory business risk decreases.

On the flipside, less control by the FDA means that US consumers need to increasingly make their own risk calculations and decide for themselves when buying wearable health tracking devices.

Ben Heubl is nuviun's data journalist who specializes in data visualization and writes about health and tech innovation. You can follow him on Twitter @benheubl.

The nuviun blog is intended to contribute to discussion and stimulate debate on important issues in global digital health. The views are solely those of the author.